Esther Pasztory – An Exotic Through and Through

Will you tell us about your origins in Hungary and moving to the US in the 50s?

I was born during the second world-war in Hungary, and I didn’t experience the war as an adult. My parents decided to escape only during the Revolution of 1956 and come to the US, so I grew up in Communist Hungary. So you could say that most of my life was divided between cultures. When I came to the US, it was divided between my Hungarian and American lives But already in Hungary I was divided. I understood what we were supposed to say and believe in the communist school, and at home I understood that my parents believed something completely different. So you might say that my origins and perspectives were divided. In America the divisions went deep. Hungarians are pessimistic and ironic, but Americans are optimistic and gush with excitement over everything.I did not fit into either fully. So I came from one world to the other. I was asked by my American culture to assimilate, which was totally impossible, even at that age. While ostensibly I assimilated into the American culture, I was always seen as an exotic.

Now, many people in my position became specialists in Hungarian art or history. I did not want to become a “professional” Hungarian. It was an African art experience that made me want to belong to the world at large, not Hungary or the US. I guess if I was thought of as exotic, I would become the most exotic thing that was imaginable, an exotic with a vengeance. I also had some naïve idea that the American Indians were the ancient culture of the Americas, kind of the way that Greece and Rome were the ancient cultures of Europe, and by studying their remains I was studying the earliest America. So it was a kind of an assimilationist act. As I grow older, the more I think the US would be a happier place if it acknowledged the contributions of the Native Americans in its history of the continent. It does not begin with the constitution. It’s actually much earlier.

It’s interesting that you put more commitment into America than Hungary.

Well, I have no real choice but to be an American. I speak Hungarian and write it, but not very well. I had an apartment in Budapest for about 10 years because I was interested in what had happened after the Velvet Revolution. But I could not assimilate there. I did not go to school there. English is my language. I may not belong totally happily and comfortably, but that’s where I belong. If I write anything, I write it for a Western audience. God knows if I could have gone into this field in Hungary. Pre-Columbian art does not exist in Hungary, and they are very pro-Western, so in a way I do better here.

When you grow up in different cultures, you have to read between the lines. In order to survive, you have to do that, otherwise you make terrible mistakes. So that’s as close as you come to my intellectual background. When you grow up in a single culture, you’re not aware of these things, because you’re not making comparisons, but I’m always making comparisons.

I don’t think about it all the time. I just live it, because there’s no other place to go to. I’ve always said that my place is the pre-Columbian world. Number one is Hungary, number two is the US, and the third is the pre-Columbian past. It’s a good place to think , where you can assimilate as a scholar. You don’t have to assimilate as a person there. I help create that world. I’m the one who helps to create the Aztec world, or the Teotihuacan world. That’s the way I see it, or how I want to see it. In that way, it is more congenial. As you put together these various cultures, you are also putting together yourself.

I became interested in this field when I was taking an anthropology class at Barnard and we were told to write on some piece of primitive art and sent to some galleries. I knew nothing about the subject, and I went to a gallery of African art and I saw these amazing little brass figures. The gallery owner explained to me that these were weights used in weighing gold dust in the kingdom of the Ashanti in Ghana. I was absolutely amazed that south of the Sahara there were kingdoms that had gold dust and little figures representing proverbs. That made me realize that I knew very little about most of the world. I was familiar with India and the East, the major cultures, but I didn’t know anything about what was considered “primitive.”

So when I went to graduate school, I decided to study “primitive” art. That consisted of all of Africa, all of Oceania from New Guinea to Easter Islands, all of North American Indian and the Amazon region of South America as well as pre-Columbian art which was kind of attached to primitive which included Mexico, Guatemala, Central America and the Andean regions. In fact this area was ¾ of the world that we studied. And it was all material that was unknown to most people.

I was fascinated by their mystery and by the fact that I could be the first person to study some of these things. I could be a pioneer. I wrote a book on Aztec art that was the first book ever written on Aztec art. The only reason I did it was because I was looking for a book with illustrations of all Aztec monuments and there wasn’t such a thing. You had to go from this book, to that book, to that article, and mine was the first book that brought all of them together. So it was the idea of finding fascinating kingdoms like the Ashanti and also being the first one to talk about their artistic aspects

Then I went to Mexico, and I saw the ruins, which were so impressive and so large, and yet they were made by people that had no metal tools. They only had stone tools, and they erected pyramids like those of Egypt. I became fascinated by how and why they did this.

And I guess alongside this there was a missionary streak. ‘How come people don’t know about these things?’ I remember being at a party with some other academics and I was explaining to someone in the Western tradition – I don’t know what field he was in – what I was doing and how I was bringing these things to life, and he turned to me and said sarcastically, ‘It must be nice to do missionary work.’ And in a way, it is missionary work.

Another thing worth mentioning, when I was in graduate school starting 1965, “primitive” studies still existed. I had friends who went to villages and tribes and studied primitivism. Globalization had not yet happened, and so we were kind of like the last generation who saw these cultures in situ and alive and going strong, making masks and using masks and so on. By the 1990s, that has disappeared. There is no place on earth that has remained authentically primitive. In New Guinea, where Michael Rockefeller disappeared and was thought to have been eaten by cannibals, there are souvenir shops in all the men’s houses. Amazonian Indians have camcorders and record themselves on camcorders. So the whole world has lost this. I came in at the very last time of this interest in recording these cultures.

~Do you kind of see a West/Non-West binary between what is considered primitive and civilized?

Well there is a West/Non-West binary between these cultures. For example, in most of these areas, artists have now become like Western artists. They are exhibited in Western places as a kind of hybrid modern/traditional style. The interesting thing is that Westerners for a long time preferred the totally traditional, and they did not want to see these hybrid styles at all. They even established schools to teach the traditional. They considered hybridity bad. But at the same time, the artists were trying to move into the mainstream of Western art and global art were not able to do it. Now they are. That barrier has fallen. But there are museums who don’t know what to do with them. For example, there is an African artist (El Anasui) who makes fantastic things out of bottle caps. It’s all abstract. His work is exhibited at the Metropolitan in the African Art gallery. It is not exhibited in the modern art gallery. There is still a search to see its “traditional” side. There is no way that these people can be considered just plain contemporary. They are still ethnic, and I think that is going to last for a while. I explored this phenomenon at Columbia in a team taught course with my colleagues entitled “Multiple Modernities”

You talked about that in an interview where you were discussing Westernized artists. Is that because of globalism?

It IS globalism. It is definitely globalism. People have computers in the remotest areas of the world. We’re all part of one culture with little local designations of where we come from. It’s all becoming aspects of one large culture. For a long time, there was nostalgia for the traditional, for here and there and, ‘They’re all different from us.’ And they’re NOT all different. All you have to do is watch the news on television, and you see Mali and Bamako. Bamako has multi lane highways just like any other place. There is no place anymore that is truly other, except in a kind of Disney representation.

Could you say more about your concept of art?

The word art is so problematic because it implies that some objects have inherent good qualities as opposed to other objects. It’s so obvious that at different times, different things were considered art. And I use words like “visual culture” to refer to all of the things of a particular culture, some of which we designate as art and some of which we don’t. And we are quite irrational because we have very specific ideas of what we consider art at any given time.

There are these African figures that have been made out of cloth, blood and feces and all kinds of other junk, and these things are placed in our museums as African art, but anything else like that in another culture will not be. There was that artist who used elephant dung on paintings who created a lot of controversy. Things have meaning. Even modest things have significance. Hallmark cards have significance. It’s just a cultural decision that makes something art.

You talked about how art is a cognitive display of the society’s own development of problem solving.

I think of art as a form of communication – a way of thinking. Hallmark cards or a Christmas cards are ways to think with.. You might think they are kitsch or at the high end of art, that does not matter Hallmark cards in the 50s become valuable “art things” because of their rarity. So all of these things become factors in what we consider art. I think of art in terms of “things,” but they always require distinctions.

I consider all of them” things,” including the Mona Lisa. But it’s very awkward to think of them in terms of things. There are critics who argue the inherent quality of art, but basically they are all things named “art” by people. They communicate more or less. Some have enormous capability for communication, others have very little. A cathedral can communicate a great deal, but a Hallmark card can communicate very little.

Will you talk about structuralism and how you use it to think about art?”

Structuralism is a theory that was popular in the 1960s when I was a graduate student. The part I borrowed, instead of looking at styles to look at things in terms of their structure. How are they organized? I found that a liberating approach and I used that as an approach to studying Teotihuacan, because it is the most mysterious pre-Columbiaan culture and because we don’t have Spanish responses about them .- as we do for the Aztecs.

You could therefore not name any of the persons depicted, but still know how they were organized. For example, you could know that they had elaborate borders around everything. You might not know anything about the meaning of the borders, but you would know about the borders as such. So you could guess that the Teotihuacán might have been interested in the separation and division of things. You could therefore have an idea of what they might have been like without knowing what their gods were like or who they were

You could actually do structural analysis of this sort to other cultures, but people don’t do it because they have other sources of information. But I think the structuralism method leads you to the subconscious, the unconscious, as in the division of the city of Teotihuacan into compounds where there is an emphasis on privacy, and that can relate very clearly to the borders that are found in art. Now, I haven’t done this for New York City, but I think these are ways that you can discover the meaning of things in terms of their structure.

Did that theory also come in handy when studying other civilizations?

I first came upon it when I was studying the Aztecs. I was very frustrated, because I couldn’t understand anything about Teotihuacan when writing my dissertation.. So I thought that if I studied the Aztecs, that would help me with Teotihuacan, because 16th century sources were available. But studying the Aztecs, I discovered that is was not in the texts but the structure of the works of art had the answers to my questions. There were obvious differences whether they were made for elite temples or ordinary temples, or the rural peasantry. The elite temples had frightening gods whereas the deities of the ordinary people dealt with fertility and water and maize and looked benign. I found that out not through the texts but just by looking at the works and discovered what seemed to be done at different times and places. I went back to Teotihuacán and looked at it structurally, and that’s where I seemed to get somewhere. That’s when I realized that there were more representations of animals than humans and why. This sounds very basic, but I think that it is the basic stuff that is mostly overlooked.

This reminds me of what you had said about how the more complex a society is, the more complex its art becomes.

Well, any art or object that deals with the social and political sphere is usually prettier and more elaborately done. It’s more elegant. Things that deal with the religious sphere are often rougher. The social world, whether that is a chiefdom, or an empire, that is where the elites are looking for objects of social significance and artistic effect. High polish is often characteristic.. In really small societies there is no distinction between social and other kinds of representations. But as soon as there is a very important kind of social world, things get finer and more complex.

Back to how you developed your interest from West African art to Inca cubism.

When I started off in this field, I was just as conventional as anyone else. I was immediately attracted to Meso-American culture for the same reason other Westerners were, because of its anthropomorphism and more or less naturalistic representation. I am a Westerner too. I was always attracted to its monumentalism and grand statues, but I was not used to seeing it –its structure, its material, its technique. The mental idea behind it. I first became interested in these through the amazing Inca rock work in the 1980’s. The Inca architectonic ideas in windows, niches, steps, the way architecture blended into natural rock, the veneration of natural rock itself, which was my first entry into the Incan field. I wrote Inka Cubism showing how, from a structural point of view, you could understand every Andean culture and that it was not comparable to Meso-America. There are obviously different ways to constructing civilizations.. In the past, they could develop in a unique and unusual way, because they were more or less isolated from each other. Now that is no longer possible.

When I started off in this field, I was just as conventional as anyone else. I was immediately attracted to Meso-American culture for the same reason other Westerners were, because of its anthropomorphism and more or less naturalistic representation. I am a Westerner too. I was always attracted to its monumentalism and grand statues, but I was not used to seeing it –its structure, its material, its technique. The mental idea behind it. I first became interested in these through the amazing Inca rock work in the 1980’s. The Inca architectonic ideas in windows, niches, steps, the way architecture blended into natural rock, the veneration of natural rock itself, which was my first entry into the Incan field. I wrote Inka Cubism showing how, from a structural point of view, you could understand every Andean culture and that it was not comparable to Meso-America. There are obviously different ways to constructing civilizations.. In the past, they could develop in a unique and unusual way, because they were more or less isolated from each other. Now that is no longer possible.

You are currently studying an artist. Waldeck?

Waldeck was the first European artist to seek out the pre-Columbian world to find fame and fortune. There were other illustrators who came with expeditions to make drawings of the ruins and then went home. Waldeck was the first who was a lone entrepreneur. He came on his own to discover the Mayan ruins and stayed in Mexico seven years.. He is mainly famous for being inaccurate, for getting it wrong. He imagined that he saw elephant trunks in the images and parallels with Hindu art.. He seems to have messed up most of it. He is considered a bad boy in pre-Columbian circles. I got into it because I was studying 18th and 19th century Neoclassic art, like David, and it seemed to me that it looked so much like Maya art , that it might have been a time for them to be introduced to the West.

A search revealed that no European artist was interested in Maya art in the same way that they were interested in African art around 1900. Then I remembered Waldeck. He was obviously not there just to record the drawings. He was obviously working as an artist, and later exhibited at the Paris Salon. I got interested in him as an artist who took these subjects as an object. I found that, in this form, Waldeck was unknown and was mostly unpublished. There was no one place that you could see Waldeck illustrations. Two main places (Paris and Chicago) had them. I saw in Waldeck a minor “Orientalist” artist who went West. Most of ipre-Columbian scholarship is a scientific story of art, While Waldeck said something about Maya aesthetics.. Other than the fact that he was a crazy guy and did a lot of lying about great expeditions that he has been on, he did a lot of interesting things. So that was the first book English language book, putting Waldeck in perspective in the intellectual context of Europe and exoticism and what it was he was trying to do.

This is he kind of work that I really like to do, to be there first to set up the questions and issues. I like being a pioneer, and with Waldeck I am making his images available for other people to study. I seem to find a topic that has been overlooked and under-appreciated.

How does putting a spotlight on an individual like this generate a larger conversation within the field?

I would say that everything I’ve done has taken a long time to affect the field. The field kind of lumbers along in its usual way and it meets up with something that I have done in left field. It takes some time. For example, the Aztec art book did not have much in the way of reviews. It kind of fell into oblivion, and it has now become a classic. Similarly with Waldeck, it will take a while. The 19th century people have to pick it up. They have their own categories and things. I expect that it will get there, but it will take a while.

What is it about your books that is different from your field?

That’s an interesting question, and I’ve never thought about it, so I’m not sure I can answer. I think, on a certain level, that I am more critical of contemporary ideas than other people. I think this gets into the personal thing of my background, of being able to see things from another perspective, a perspective that is very productive but not currently popular. I’m amazed – the extent to which scholars follow a particular line and that there are not more idiosyncratic and dissonant voices. I will also say that among my graduate students, most of them essentially follow what is traditional in the field.

As to what all of these books share, I did them all one by one, and I wasn’t thinking of them as a philosophy of art, but I think they are all permeated by the idea that “art” is a man-made concepts and just a special mental category of “things.” I have been described as a person who does very good syntheses. I enjoy contrasting too. I find it very hopeful to think of two cultures because they tell you what is more important one rather than the other.

I was very interested in Asian culture, and I considered going into it in college, so I am interested in looking at things from a Bird’s Eye View. A lot of my colleagues would hesitate. I know I am not a specialist, but I know some basic things and you can make comparisons. I may be wrong, but I may be right. In that sense, I have a global vision, and most of the people I deal with do not. I will not shy away from comparing Inca rock art and Japanese gardens. Despite the differences between them, they have more ideas in common, and that seems to me worth saying or debating, even if I am not a Japanese garden expert.

Will you talk about your most recent work?

It’s a small book and its entitled Aliens and Fakes: Popular Theories about the Origins of American Indians.” It deals theories such as extraterrestrials and transpacific contexts and all the kinds of theories that experts make fun of.. I’m not so much interested in debunking them as seeing why readers are attracted to them. I’ve basically come to the conclusion that part of the problem with pre-Columbian studies is that these are not subjects that are studied in high school. They are studied occasionally in college or in primary school. People don’t know much about it. They know something about Greece and Rome, but they don’t know about American Indians. I have a section basically about “What You Should Know, about pre-Columbian Art”” and I have a basic list of monuments you might know. My feeling is that until it’s something that is taught, it remains a kind of crazy mystery.

It’s a small book and its entitled Aliens and Fakes: Popular Theories about the Origins of American Indians.” It deals theories such as extraterrestrials and transpacific contexts and all the kinds of theories that experts make fun of.. I’m not so much interested in debunking them as seeing why readers are attracted to them. I’ve basically come to the conclusion that part of the problem with pre-Columbian studies is that these are not subjects that are studied in high school. They are studied occasionally in college or in primary school. People don’t know much about it. They know something about Greece and Rome, but they don’t know about American Indians. I have a section basically about “What You Should Know, about pre-Columbian Art”” and I have a basic list of monuments you might know. My feeling is that until it’s something that is taught, it remains a kind of crazy mystery.

I’m not saying anyone is an idiot. I’m saying that these aspects of the myths might have seemed reasonable to people and this why they believed it. Because in the vacuum of not knowing the facts, any kind of interpretation goes. So I have another kind of missionary zeal: that something about Native Americans needs to be taught in American schools in order to understand what kind of continent we live in. Yes. It’s making a statement about the importance of Native American studies for Americans

This book, in a way, grows out of my graduate student days. The man I studied with, Douglas Fraser, really believed that a lot of pre-Columbian cultures came out of China and India through transpacific contacts, and he had his students researching a bunch of”transpacidic” topics. I don’t know if I believed it or not, but I did what I was told. There were a lot of conferences on transpacific themes in those days. Then, in the intervening years, “transpacific” became a dirty word. You couldn’t even mention it without people thinking you were a complete idiot. I had a lot of ideas about those days and I thought, well what is wrong with them? I researched it and saw it as a phenomenon linking it up with the educational system here.

Did you see them as interrelated in a way that goes beyond academia?

Except for my academic life, I am in touch with ordinary people. Even in my field, my colleagues, who are great experts in their fields, have no idea about pre-Columbian art. The difference is that in the good old days they would admit that they had no idea. In this culture, of globalization educated people pretend to know a little something about “pre-Columbian” and “primitive” but know very little. All these great pre-Columbian centers are unappreciated except for large groups of people making up crazy theories, rather than for what they are. But I was interested in using the crazy theories as a hook. That’s what gets you into the book.

Academic research always has a way of making the material inaccessible. It’s either written with jargon or in such a way to keep you out. I’ve always tried to be comprehensible, and sometimes even colloquial, so that people can read the stuff you like without reading some academic tone. Sometimes that works better than other times. Many times people will come up to me after lecture and say, ‘Thank you for making it accessible.’ I find that more touching, the fact that it is readable. I think that’s important. The thing about jargon and theories is that after their fashion is gone they become ridiculous.

What would you want your lasting contribution to be?

Every project that I’ve ever done has been a unique project. One book does not build on another book. At least, I’m not aware of what general theme they all suggest.

I think there is something about valorizing American Indian cultures as being more complex or as being more valuable, as places that tell us about ourselves and are a part of ourselves but we are denying them. I am making things visible. I make Waldeck visible. I make Teotihuacan visible, so that you can relate to them. I invite the reader to relate them to your culture, where so far they’ve been an exotic fringe, and I give them a rational existence. I give them a role in the intellectual world.

I definitely normalize the Aztecs. When I talk about human sacrifice, I talk about it globally, say what it is and what it does rather than emphasizing the monstrosity of the Aztecs. I guess it’s a commitment to the underdog, just like Waldeck, who is thought of as so terrible and who I revalorize in a certain way. I grew up with an underdog identity. Hungarians see themselves as having been victimized by Turks, Austrians and Russians in that order.. I come by this rather naturally. I’ve never been tempted to study someone like Michaelangelo. I like Michaelangelo, but he has been idolized for many centuries, so he doesn’t need me to idolize him anymore. So I don’t need to find any treasures in the museum, in fact, by the time when things are in a museum I sort of lose interest. It’s a part of me in a deep sort of way.

I am not trying to destroy Western Art but perhaps staking it off the pedestal.I am trying to set up other things next to it. There’s nothing wrong with the Mona Lisa. I just want to put it in context .There’s a whole universe of other things to look at and think with, so let’s just give them a chance. I think it’s just putting Western Art in its place, putting it in context. I’m putting it in context with cultures that have written texts. There are other contexts where other things fit. .

Are you planning to do anything special when you retire ?

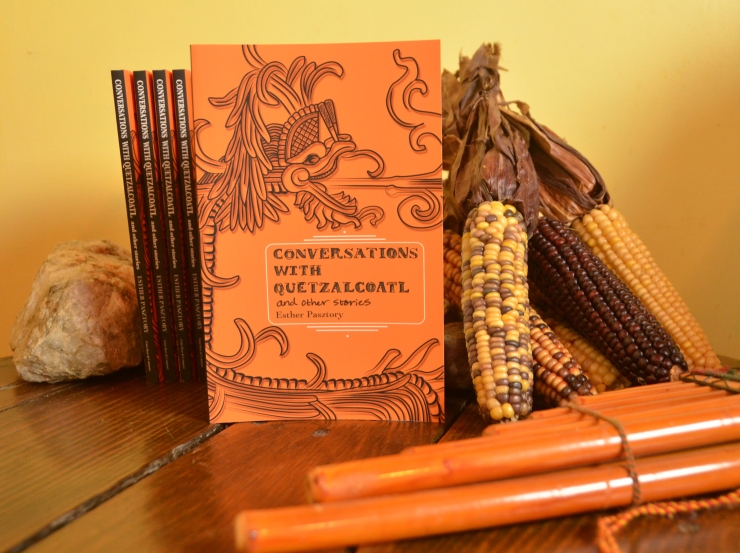

I hope to write more fiction. Some years ago I published a “pre-Columbian” novella and Colonial short stories entitled Daughter of the Pyramids. In press is another volume of short stories entitled Conversations with Quetzalcoaatl. I have also written a short memoir, Remove Trouble from your Heart. Based on these, I would like to write a fictionalized memoir with a larger scope.

I hope to write more fiction. Some years ago I published a “pre-Columbian” novella and Colonial short stories entitled Daughter of the Pyramids. In press is another volume of short stories entitled Conversations with Quetzalcoaatl. I have also written a short memoir, Remove Trouble from your Heart. Based on these, I would like to write a fictionalized memoir with a larger scope.